Some Thoughts on Government Health Recommendations

As I type this, the US is coming out of 18 months of the Covid-19 Pandemic and the public response to said pandemic. The response has probably done as much damage as the virus itself, and as of October 2021, it's hard to see how the wounds in the nation will be healed from either. And I have a lot to say about that, but that'll come later. I want to build up to that by looking at a few other examples of public health recommendations.

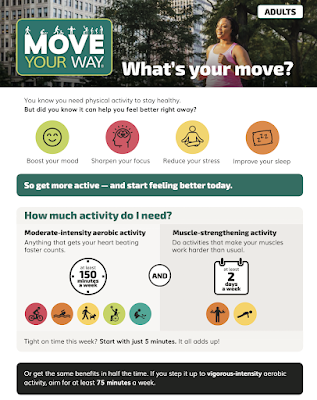

The Covid19 recommendations are surely the most successful public health campaign of all time. Everyone has heard of the recommendations -- wear a mask, wash your hands, keep your distance -- whether they agree with them or not. But for now I want to look at one of the least successful public heath initiatives: the Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults.

It's well known that Americans are fat and lazy. As to the "fat" part, that would be covered by the Nutrition Guidelines, which are even less successful. But to focus on the "lazy" part, the Physical Activity Guidelines' goal is to get everyone moving. According to the guidelines own preamble, roughly 20% of Americans move enough, so there's a lot of work to do.

I'd estimate that every public initiative like this has to be equal parts medical science and public relations. In other words, the initiative has to be

- It has to be easy to understand and remember.

- It has to be within the reach of most people.

- It has to be widely communicated.

- It has to be be medically effective.

The Guidelines are relatively easy to understand.

- Get 150-300 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75-150 minutes of vigorous activity per week or some combination of the two.

- Do resistance or strength exercises twice per week.

I'd argue that the terms "moderate" and "vigorous" are vague and probably useless. "Moderate" intensity is defined as an intensity where you can talk but not sing presumably because your heart rate is up and you are starting to breath hard and don't have the wind to sing out loud. "Vigorous" intensity is where you can only speak a few words at a time because you are breathing so hard. A brisk walk would be "moderate" while running would be "intense".

Those terms are problematic because I would estimate that just about everyone will overestimate their level of activity. While walking can count as a moderate activity, it probably doesn't. You really need to do a brisk walk for that to count, but unless you have a smartwatch that tracks heart rate you won't know that. On my Apple Watch, for instance, I can easily walk for 30 minutes and only get 5 "Exercise Minutes" out of of the activity, especially if I'm walking my dog and stopping every 20 seconds so he can check other dog's pee-mails and leave his own. My Garmin is even harder to please. But if I didn't have either watch, I'd likely count the whole 30 minutes as part of my "Activity" time.

However, if you can convey what a "moderate" activity is, then I think the guidelines are relatively easy to understand. While I respect the fact that "150 minutes" is a nice round number, I'm not sure that people really think about time that way. I'd probably prefer "30 minutes per day" but both are easy enough to understand.

I think the guidelines also score well on the "achievability" metric. The guidelines are for minutes of activity, not calories or METs or hitting a specific heart rate zone, because you need special equipment to measure those things. Note also that they don't mention getting a specific number of steps every day, because not everyone can walk. The type of activity is not mentioned at all. You can run, walk, swim, lift weights, do push ups, bike, or just about anything you can think of to get moving. In fact, there is a slick website where you can plan out how you're going to get your minutes in. For instance if you already spend a certain amount of time each week doing yard work or house work, those minutes count and you only need to exercise the balance of the time.

The general impression of the Move Your Way website is that even if most people are not meeting the guidelines, they are not far off. While there are outliers that watch TV or play video games all day, most people would engage in activities that would get them maybe 50% of the way there and they can meet the guidelines by adding a minimal amount of exercise (defined as a purposeful bout of activity, not activity done while working). So it's not an overwhelming goal. You don't have to run a 4 minute mile or swim the Mississippi river to get health benefits.

Technically you don't need to spend any money to achieve these goals. You don't even need a watch (not a sports watch or a smart watch, but any watch at all). You can look at the wall clock before you start on your walk or run or basketball game, then look at it afterwards to see how many minutes it was and after you do that a few times, and assuming you haven't changed things up, you don't even have to look at the clock. However, if you get into fitness, you'll eventually buy the accessories needed, like shoes or workout wear or that watch I keep bringing up. But it's not a requirement. Anyone can do it.

So i think the Physical Activity Guidelines meet the first two criteria. I don't like the "moderate" and "vigorous" categories, but I don't really know what could be changed. So I like it.

The Physical Activity Guidelines fail miserably in the "widely known" camp. Though there are miscellaneous influences that could get people moving (The Play 60 campaign that the NFL promotes during games being a prime example, as well as the various fitness challenge shows on TV), none of these are presented as part of a coordinated campaign and hardly anyone knows about the actual 150 minutes per week or the broader Activity Guidelines program. Nor is anyone interested in talking about it. Doctors rarely bring it up. Nurses rarely bring it up. By way of comparison, when I got to the doctor today, he wants to know if I got my rona vaccine and will inject me himself if I haven't. Likewise during flu season they'll give me a shot right there in the office if I haven't already gotten one. But they never bother themselves to know how much I'm moving. Even if I have a condition that could be improved by moving more like high blood pressure or diabetes. If the Activity Guidelines were treated like the Covid guidelines, every business would have posters promoting activity and there'd be PSA's every hour on TV telling people to start moving (ironically). Every video on YouTube and every post of Facebook would have little links for more information about getting your minutes in.It's hard for me to believe that the Government, which spends money like a drunken sailor on the best of days, draws the line and buying advertisements to promote activity. But there is is. So they get a passing grade on the 1st and 2rd criteria and a failing grade on the 3rd.

Are the guidelines medically sound? There is a rather exhaustive science report released along with the guidelines themselves that details all the health benefits of physical activity. But the headline figure can be found on page 35 of the report itself

An interesting observation is that no one that I'm aware of disputes these findings. Some people might quibble that the guidelines don't go far enough (they might prefer 200 minutes per week, or prefer that the activity be done in bouts of at least 10 minutes). In fact, many countries around the world and the World Health Organization have the same criteria of 150 minutes of moderate exercise per week. Not only governments -- who are not known for independent thinking -- but private organizations like the American Heart Association and the American College of Sports Medicine promote these same guidelines. There's a shocking amount of uniformity, which I would take as a sign that most medical professionals, when presented with the data, agree at least generally with the recommendation, though I can't rule out groupthink. (However, if you live in Japan, you'd better have a comfortable pair of walking or running shoes. They want 60 minutes of activity each day.)

Beyond the simple relationship between exercise and mortality shown above, the HHS has summarized the data for various medical conditions. And this is, I think, the most admirable action of the whole program. The HHS has put its cards on the table with chapter and verse about how they settled on 150-300 minutes/week.

However, when we look at this data, some things become apparent. Let me pick a few examples: Breast Cancer, Bladder Cancer, High Blood Pressure.

According to the Science Report, about 125 out of 100,000 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer each year. There are approximately 100 million adult women in the US, so that implies 125,000 women diagnosed with breast cancer. An arresting thought. It's actually more than that according to the breastcancer.org, but I'll stick with the Science Report's numbers. They list a series of studies, all with different amounts of relative risk, but a reasonable average is 0.85. A relative risk of 0.85 means that a person given a treatment has an 85% of whatever adverse reaction you are studying vs a person not given the treatment. In this case, a woman who exercises has an 85% chance to get breast cancer vs one that doesn't.

That is great news! Anything that reduces the risk of breast cancer is worth knowing about. But what does it actually mean? If we use the Science Report's statistics, 125 / 100,000 women will get breast cancer. An RR of 85% means that 106 women will get breast cancer if they all exercised.

Is 106 that much different from 125? I don't really know. It's a lower number, and damn sure better than if the number went up to 144, but if you're in that 100,000 group you might ask for more assurances than that. While the relative risk of not getting breast cancer is 19 / 125 but the absolute risk reduction is 19/100,000. And that's a little harder to get excited about.

Applied to the entire country 18,750 women will avoid breast cancer if they all exercised. That's a lot of women who won't have their lives turned upside down. And it's a good thing! But it kind of looks like a marginal benefit which doesn't really add up until you apply it to an entire population.

Breast cancer is the number 1 cancer in the US. Bladder cancer is quite a bit lower in incidence. According to the Science Report, 20 people per 100,000 get bladder cancer. I don't know what population that's based on. Mostly men over 50 get bladder cancer, but women can get it as well. But if I just picked 100 million (the total adult population in the US is 200 million, but I'll cut that in half to account for the prevalence among older adults), that would mean 20,000 per year, which again seems low to me, but the absolute numbers don't matter that much. Conveniently, bladder cancer also gets a 15% reduction in incidence with exercise but since the number of cases is lower in the first place, that benefit is also lower. Now the incidence goes from 20 / 100,000 to 17 / 100,000. Bladder cancer is actually one of the more expensive cancers due to the treatments and recurrence so saving 3,000 people per 100 million actually does add up to a good amount of money. Plus the people that don't have to go through that will definitely appreciate it but it's still only 3 people per 100,000.

In the case of High Blood Pressure, the Science Report the authors claim that exercise will lower blood pressure by 3-5 mmHg / 1-4 mmHg (systolic/diastolic). Even with the moderate improvement among healthy and pre-hypertensive subjects, the authors of the science report claim a reduction in coronary heart disease by 4-5 percent. But how many people with normal blood pressure get coronary heart disease?

Again, it's a good improvement, and applied across the entire population will result in thousands of people avoiding serious disease. But it's hardly an important factor for an individual person.

The strange part of the report is that there are clear benefits of exercising if you already have high blood pressure. In my experience, physical activity lowers blood pressure by at least 10/5 (systolic/diastolic), and there are studies that confirm that. Studies have shown in hypertensive people, exercise is as good as the first-line dosage of blood pressure medication. In fact, I've been able to stay off of high blood pressure medicine by running and biking every day. But for some reason, the report barely mentions that.

The examples can be applied across the board. In each case, there are real, statistically significant benefits, but in each case one could argue that they aren't really practically significant. But if applied to a large group, like the population of the United States, great cumulative benefits could be achieved. And perhaps that's one of the reasons why your family doctor doesn't spend a lot of time encouraging an exercise routine. He is not interested in the health of the population as a whole, he's interested in the health of the patient in his room, and for most people, the quickest answer is a pill.

Before anyone things I'm picking on these guidelines too much, I definitely am not. I'm actually a big believer in them and wish that they were encouraged more. While there's a small reduction in cancer risk and a slight improvement in heart health, and a modest improvement in mental health and so on, when you add them all together, exercise can really make a noticeable improvement in a person's quality of life. And, after all, what do you expect? Exercise is free, after all. And 150 minutes of exercise is within the grasp of most people. Maybe we should encourage a greater level of exercise. But that might scare people off. And we haven't even discussed diet or other habits. Even if exercise has limited value, it's cheap and easy. Why not? What does it hurt (besides your muscles)?

Comments

Post a Comment