I wanted to get into the specific non-pharaceutical interventions that were put in place around Novel Coronavirus, but I decided that it might be helpful to start with another viral outbreak that's not quite so "novel". The annual season of illness known as "cold and flu" season.

To start, every year starting around November the incidence of colds and the flu increases in the United States. In fact, the nasal congestion and cough associated with the cold is so characteristic of the winter months, that the disease took it's name from the cold weather of winter and many people think that the cold (disease) is caused by the cold (weather).

Of course, the cold is caused by any number of viruses, including coronaviruses. However, if the cold is not caused by exposure to cold weather, there is still the question as to why it is so prevalent during the winter months. There are a number of possibilities.

- During cold weather, people spend more time together indoors where it's easier to spread the virus form one person to another.

- Winter weather is more conducive to viral spread. Perhaps the virus can survive longer in cold, dry air than it can in warm, moist air and that give it more time to spread from one person to the next.

- People's immune system is depressed during the winter. This has a few sub-possibilities.

- Less direct sunlight in winter means less Vitamin D, which is essential for a healthy immune system.

- Exposure to cold dry air may affect blood flow, specifically to the nose which may impair the nose's ability to block pathogens from getting into the body.

- Repeated exposure to hot and cold days can increase the likelihood of spread. In fact, most of the speculation on the cause of colds among the general public that I hear is not that a bout of (for instance) 30-degree days will cause a cold, but having a high of 35F one day and a high of 65F a few days later followed by a high of 30F a couple of days after that (which happens often enough where I live) is what makes people sick. Why?

- The constant change in temperature makes is hard for people to dress appropriately. Someone may leave for work in the morning with a light jacket only to find the temperature is much colder than expected when he leaves for lunch or to come home.

- Since the air is still dry at this time the virus can still survive longer and a person's behavior during the warmer spells might put him at increased risk.

- Winter weather may expose a person to additional allergens (for instance dust or pet dander that a person may avoid by being outdoors instead of indoors when visiting friends) which cause nasal congestion, which in turn causes a person to breath through his mouth which gives any viruses an easier route of infection.

And there are probably other reasons. However, it's important to realize that the cold is caused by a variety of viruses, so any speculation on the survivability of a cold virus in the cold weather has to apply to all of them. Or they have to be all present at the same time and the winter weather simply favors the viruses that are adapted to it.

The same speculations can be applied to influenza. However, even in the cold and flu are coincident in time, they are different viruses and for some reason the "common" cold lives up to its name and is

more common than the flu. Note the nice mixing of units in that article. "Each year, Americans get more than 1 billion colds, and between 5 and 20 percent of Americans get the flu". "One billion" vs "4-20 percent". Carl Sagan for the win. Since there are 330 million Americans, that works out to every American having a 300% chance of getting a cold vs a 5-20% chance. Or 1 Billion colds vs 0.016 - 0.066 billion flu infections. However, the flu is deadly to certain people, with

hundreds of thousands of hospitalizations and tens of thousands of deaths each year (not this has a different estimate of flu incidence than the NIH paper) so even with the much lower incident rate, it is the more serious infection.

To a certain extent, the exact reason the cold and flu are more prevalent in the winter months doesn't matter. As long as the diseases are treatable, one approach is to simply plan for the outbreak and stock up appropriately. Grocery stores and pharmacies stock up on cold and flu remedies during the summer and early fall. Doctor offices get ready for the onslaught and media outfits prepare their flyers and PSA's for avoiding the flu.

On the other hand, knowing the mechanism can improve prevention. Looking at the list I put above, if it could be established that, say 20% of the cold and flu infections could be avoided by increasing Vitamin D levels or by placing a humidifier in the home, that would be a huge impact. At the upper end of the CDC's range, that would be over 140,000 fewer hospitalizations and 10,000 fewer deaths and many more fewer grieving families. Even if many of those deaths are among the very old who could be expected to pass on within a year anyway, there's a very large difference to the patient and the family between dying peacefully at home surrounded by your family and dying in a hospital with tubes and wires connected to you. And it's a cheap intervention. Vitamin D is basically free and humidifiers cost less than $50 each, of course multiple small humidifiers may be required depending on the size of the home, and outfitting an entire school with humidifiers would be a challenge.

Studies have been done, but not enough studies and the results are complicated. Vitamin D may only have a role for those already deficient, for instance.

Two areas are commonly regarded as incubators for the flu: Schools and Nursing Homes. It's possible that most adults get the flu when their kids bring it home from school and stories about entire families being ill with the flu are common. Nursing homes are a particular concern. It has been

reported that during outbreaks, 33% of nursing home residents may contract the flu, and over 6% of them will die, which gives a case fatality rate of around 5%.

Given the severe nature of the flu, and the predictable time frame that the flu will hit, nursing homes have guidelines for prevention and management. The CDC has a

large amount of information on how health care providers, including Long Term Care Facilities should deal with the flu. Most of it is common sense: keep people who are sick out of the facility, exercise good hygiene, including staff changing PPE between rooms. Interesting, facility-wide lockdowns for nursing homes is not recommended. Instead, sick patients should be isolated from everyone else. In my own personal experience, when the flu hits my mother's nursing home, they implement a stricter lockdown policy than is recommended in the CDC documents. I can't say that they are doing anything wrong with that policy: it may be a facility-specific best known method, but it's interesting in light of the rona (which I'll get to eventually).

However, the CDC's first and favorite recommendation is to get the annual flu shot (which I do, in the interest of disclosure). The CDC has a

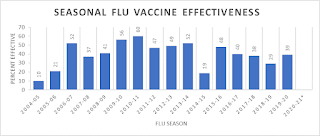

whole section of their site devoted to the features and benefits of the flu shot. In it, they repeatedly list the flu shot as the number 1 thing you can do to prevent the flu. It's usually described as the "best thing" to prevent the flu and in any list of preventative measures, its listed first. So you'd think the effectiveness is pretty high. But actually, it seems to average

around 40%.

In my earlier articles about exercise and nutrition, the benefits to health seemed to average around 20%, so 40% is better than that.

Since the most vulnerable are the elderly, it's worth considering the effectiveness of the vaccine among that particular group of people, and there's evidence that it's possibly

as low as 20%. The CDC's own data doesn't quite confirm that there's an overall decrease in vaccine effect among the elderly, but it doesn't refute it either. For the

2019-2020 season, there's no difference.

But for the

2016-2017 season, there maybe was (maybe not).

So the vaccine effectiveness is the best thing you can do, but it may not be that great. Of course, both of those statements can be true at the same time. And the combination doesn't mean that the vaccine is worthless or that people shouldn't get it. I find a lot of stuff on the CDC's website, but not a lot that I want to find, but for the

sake of argument, let's say that the flu shot is 40% effective against GETTING the flu and it's 30% effective against DYING from the flu. In another

CDC paper, they estimated that in the 2019-2020 flu season

35,000,000 people got the flu

380,000 went to the hospital

20,000 died.

That is roughly 10% of the population getting the flu, 11% of those that get the flu going to the hospital and a 5% risk of death among those hospitalized with the flu (assuming everyone that dies goes to the hospital) or a case fatality rate (of all flu patients) of around 0.05%. That's of course with the current immunization regime in place. If 50% of the population gets vaccinated (about right) and the vaccine is 40% effective, that means that if no one got vaccinated, I'd expect 20% more people to get sick, or 7 million for a total of 42 million. And if the vaccine is 30% effective against dying from the flu, I'd expect

42 million * (0.0005*0.3) or an extra 6300 to die for a total of 26300. That's a lot of people, and the risks of the flu shot are low so there's no reason not do get it.

The risk to businesses is a little easier to visualize. Any company is going to be impacted by 12% of their workforce being out sick. They won't all be out at the same time, of course, but the disruption in business activity can be acutely felt. Managing an outage of 6% would be much easier, which explains why a lot of businesses provide free flu shots on-site.

However, just like in the case of the physical activity guidelines, the benefits to a given individual are also low. A given person has a 10% chance of getting the flu, and with a flu shot he has a 6% chance, which is hard to visualize. And if he does get the flu, he has a 0.05% chance of dying (assuming he's young and healthy) and with the flu shot he has a 0.035% chance of dying. So, the risk goes from small to even smaller. But things can get bad quickly. If someone's child comes home from school with the flu, the odds of getting the flu are not 10%, they are probably closer to 80%, so the flu shot would bring that down to 48%, which is much easier to visualize.

Comments

Post a Comment